Climate change is here—and impacting all aspects of Vermont life.

Data for the past several decades show long-term shifts in temperature, precipitation, and the risks of certain types of severe weather. As climate change unfolds, it is important to understand the impacts globally and locally here in Vermont.

Causes of Climate Change

The release of heat-trapping greenhouse gases, particularly carbon dioxide (CO2), has increased the heat in the atmosphere. Greenhouse gases act like a transparent blanket around the Earth—allowing sunlight to reach and warm the air, ground, and oceans but preventing heat from leaving the atmosphere into space. Although greenhouse gases are a natural part of the atmosphere, human activities such as burning fossil fuels have drastically increased their abundance (Vermont Climate Assessment, 2021).

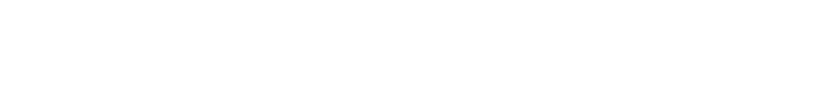

In Vermont, the largest sector of emissions is transportation, followed by building thermal, agricultural, industrial, electrical, and waste management processes.

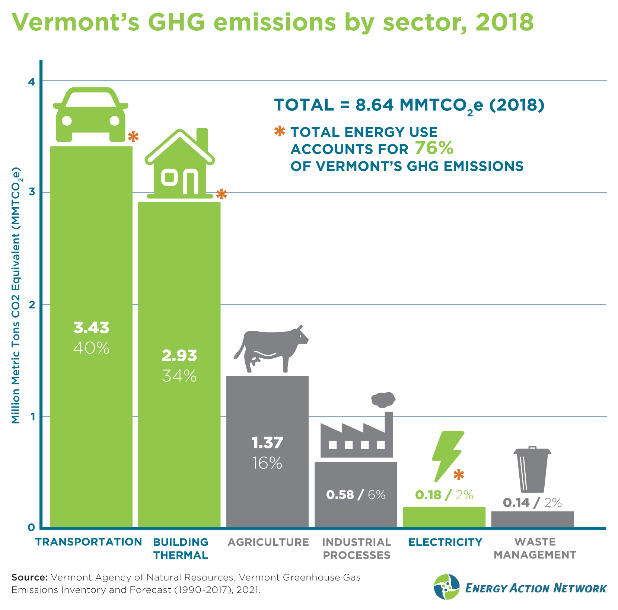

Vermont’s Global Warming Solutions Act requires a reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions

Vermont's Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Inventory

is the annual gross account of GHG emissions in Vermont. Vermont's GHG Inventory is developed by the Agency of Natural Resources - Climate Action Office.

Gross GHG emissions accounting is the estimate of the greenhouse gas emissions totals that account exclusively the emissions and do not account for the effects of carbon sinks (e.g. sequestration). This is different from net emissions accounting which includes both the gross estimates of emissions produced as well as the carbon sinks (e.g. CO2 removed from the atmosphere through sequestration).

Read Vermont's most recent GHG Emissions Inventory and Forecast report (1990 - 2020) here.

Read the GHG Emissions Inventory and Forecast report Methodology document here.

CLIMATE CHANGE EFFECTS

- Temperatures in Vermont have risen about 3°F since the beginning of the 20th century. For context, the average global temperature of the Last Glacial Maximum (otherwise known as the ice age) of 20,000 years ago was 6 degrees Celsius (11°F) cooler than today.

- The last 11-year period (2010-2020) was the warmest 11-year period on record. If emissions are not cut, historically unprecedented warming is projected to continue through this century.

- The intensity of extreme winter cold is already decreasing with Vermont’s freeze-free period lengthening by three weeks since 1960. On average, lakes and ponds are thawing one to three days earlier per decade.

Rising Temperatures

Increased Precipitation

- Annual average precipitation has increased nearly 6 inches since the 1960s, with the largest increases occurring in mountainous regions of the state.

- Winter and spring precipitation is projected to increase throughout this century and warming will increase the proportion of that precipitation that will fall as rain.

- Heavier rainstorms will have far-reaching impacts on our natural and human communities, impacting farm and forestry operations and causing damage to homes, roads, and bridges.

- The Halloween storm of 2019 produced 3–5 inches of rain in a single day, broke multiple precipitation and temperature records, led to extensive flooding, and caused over $6 million dollars of damage to infrastructure across the state.

- Climate change is expected to continue exacerbating the threats that invasive plants, insects, and diseases already pose to the health of Vermont’s forests. These threats are compounded by other climate-related factors, such as worsening storms and increasingly irregular precipitation, with drought as a factor too. Although effects vary among species, in many cases warming trends enable invasive species to spread faster by decreasing winter mortality and increasing reproduction rates.

- Drought events in Vermont range from severe multi-year droughts that impact the entire state, to shorter lived, more frequent, localized events. Vermont experienced its most intense drought since the start of the US Drought Monitor during the week of September 29, 2020, when severe drought conditions impacted a third of the state.

- Increases in heavy precipitation jeopardize water quality in Vermont. Storms produce large runoff events that contribute to erosion and nutrient loading. Combined with warm temperatures, this creates favorable conditions for cyanobacteria blooms.

Environmental Damage

Biodiversity Impacts

- As climate change worsens, 92 bird species of Vermont, including the iconic common loon and hermit thrush, are expected to disappear from the landscape within the next 25 years.

- Increasing warming trends are expected to result in an increase in white-tailed deer population and a mirrored decrease in moose population, which may have long-term impacts on Vermont’s forest composition.

- Heavier rainstorms will have far-reaching impacts on our natural and human communities, impacting farm and forestry operations and causing damage to homes, roads, and bridges.

- As warming trends reduce the severity of winters, the subsequent warming waters will have adverse effects on lake and river systems, including increased risk for harmful algal blooms (HABs) and reduced overall biodiversity and health in lake ecosystems.

- Individuals who are children, over 65 years of age, of low socioeconomic status, Indigenous, or have previous health issues are more vulnerable to the health effects of climate change.

- Warmer and more moist temperatures in Vermont are likely to create more habitat for disease-carrying ticks and mosquitoes.

- Decreases in air quality will exacerbate existing chronic diseases and decrease water quality.

- Mental health is inextricably linked with environmental health. Impacts from climate change could contribute to mental health challenges.

Public Health Impacts

Agriculture and Food Systems Impacts

- Vermont’s climate is already changing in ways that benefit its agricultural system, including longer growing periods (freeze-free periods lengthened twenty-one days since early 1900s) and milder temperatures (annual average temperature increase of 2°F (1.1°C) since the 1990s), allowing farmers to experiment with new crops or practices not previously viable in Vermont.

- The changing climate also brings agricultural setbacks, such as negative impacts on fruit-bearing species like apple trees that require a sufficient over-wintering period for success in the next growing season. The maple syrup industry is also at risk due to variations in winter temperatures.

- Climate models predict tougher growing conditions due to greater variability in temperature and precipitation, including heavy precipitation and drought leading to crop damage and failure.

- All sectors of Vermont’s economy – from tourism, to forestry, agriculture, maple sugaring, and recreation will feel the impacts of climate change.

- Vermont may see an increase in summer “seasonal climate refugees” as the rise in temperatures nationwide draws visitors looking to escape extreme heat.

- By 2080, the Vermont ski season will be shortened by two weeks (under a low emissions scenario) or by a whole month (under a high emissions scenario), and some ski areas will remain viable.

Economic Impacts

All data points and impacts listed above are from the 2021 Vermont Climate Assessment or the 2022 National Climate Assessment - Vermont State Climate Summary